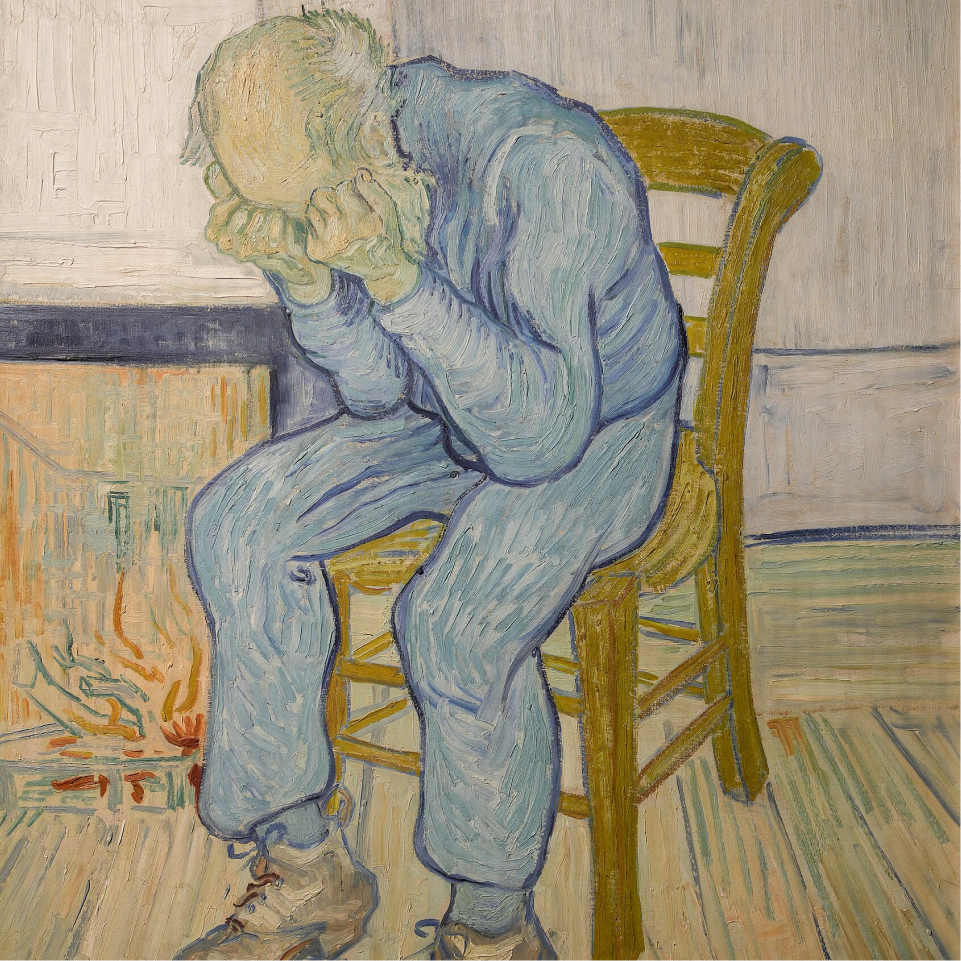

What should we do when we fail?

Jewish Talmud on Pairing Words with Action

The Life Worth Living Team

"Confession alone is futile, but one who also abandons his transgressions will receive mercy."

Listen on

Confessions and apologies are often necessary, but repentance requires action.

When we wrong someone, we generally apologize. We express remorse with our words and reassure that the harmful actions won’t happen again. But don’t words need to be paired with action? The Jewish rabbinic text, the Talmud, considers this question, explaining that one must also change their ways in order to truly repent:

[.alt-blockquote]Similarly, Rav Adda bar Ahava said: A person who has a transgression in his hand, and he confesses but does not repent for his sin, to what is he comparable? To a person who holds in his hand a dead creeping animal, which renders one ritually impure by contact. As in this situation, even if he immerses in all the waters of the world, his immersion is ineffective for him, as long as the source of ritual impurity remains in his hand. However, if he has thrown the animal from his hand, once he has immersed in a ritual bath of forty se’a, the immersion is immediately effective for him. As it is stated: “He who covers his transgressions shall not prosper, but whoever confesses and forsakes them shall obtain mercy” (Proverbs 28:13). That is, confession alone is futile, but one who also abandons his transgressions will receive mercy. And it states elsewhere: “Let us lift up our heart with our hands to God in Heaven” (Lamentations 3:41), which likewise indicates that it is not enough to lift one’s hands in prayer; rather, one must also raise his heart and return to God.[.alt-blockquote]

[.alt-blockquote-attribution]From the Babylonian Talmud, Taanit 16a:14–15[.alt-blockquote-attribution]

Questions to Consider

- How might this passage suggest we see the differences between admitting guilt, apologizing, and repenting?

- What are we striving for in repentance? Forgiveness? Trust? Transformation?

- Does apologizing or admitting one’s guilt mean anything apart from repentance? Why or why not?

- Can you be forgiven before (or without) repenting?

- What do you do when someone apologizes but doesn’t actually change? How do you hold them accountable?

- Do you consider your sins as things that place distance between you and God? How do you travel back to God in the wake of sin?

- Who do you actually answer to in moments of failure? God? Your family? Yourself?

Context

- Taanit, from the Babylonian Talmud

- Chapter 9: “When We (Inevitably) Botch It,” from Life Worth Living: A Guide to What Matters Most

When we wrong someone, we generally apologize. We express remorse with our words and reassure that the harmful actions won’t happen again. But don’t words need to be paired with action? The Jewish rabbinic text, the Talmud, considers this question, explaining that one must also change their ways in order to truly repent:

[.alt-blockquote]Similarly, Rav Adda bar Ahava said: A person who has a transgression in his hand, and he confesses but does not repent for his sin, to what is he comparable? To a person who holds in his hand a dead creeping animal, which renders one ritually impure by contact. As in this situation, even if he immerses in all the waters of the world, his immersion is ineffective for him, as long as the source of ritual impurity remains in his hand. However, if he has thrown the animal from his hand, once he has immersed in a ritual bath of forty se’a, the immersion is immediately effective for him. As it is stated: “He who covers his transgressions shall not prosper, but whoever confesses and forsakes them shall obtain mercy” (Proverbs 28:13). That is, confession alone is futile, but one who also abandons his transgressions will receive mercy. And it states elsewhere: “Let us lift up our heart with our hands to God in Heaven” (Lamentations 3:41), which likewise indicates that it is not enough to lift one’s hands in prayer; rather, one must also raise his heart and return to God.[.alt-blockquote]

[.alt-blockquote-attribution]From the Babylonian Talmud, Taanit 16a:14–15[.alt-blockquote-attribution]

Questions to Consider

- How might this passage suggest we see the differences between admitting guilt, apologizing, and repenting?

- What are we striving for in repentance? Forgiveness? Trust? Transformation?

- Does apologizing or admitting one’s guilt mean anything apart from repentance? Why or why not?

- Can you be forgiven before (or without) repenting?

- What do you do when someone apologizes but doesn’t actually change? How do you hold them accountable?

- Do you consider your sins as things that place distance between you and God? How do you travel back to God in the wake of sin?

- Who do you actually answer to in moments of failure? God? Your family? Yourself?

Context

- Taanit, from the Babylonian Talmud

- Chapter 9: “When We (Inevitably) Botch It,” from Life Worth Living: A Guide to What Matters Most

Pairs Well With

- Virtue ethics

- Consequentialism

- Christian pietism

Pairs Poorly With

- Nietzsche's morality of nobility and doctrine of total recurrence